Grapes of Wrath – 2018 Edition

Riding Route 66 seemed like a great time to read The Grapes of Wrath.

The changing geography fitted nicely into understanding both the fictional lives of the Joad family and the experience of the migrants in the 1930s. All the places mentioned in the book are still there, obviously, but some have fared better than others – those dependent on Route 66 like Glenrio, Texas are now dead; those built on agriculture or oil like El Reno, Oklahoma are doing just fine today.

The themes of the book are as relevant today as they were 80 years ago — In the late 1930s dust bowl, small farmers were driven from their land by climate change, industrial agriculture, and debt. Five hundred thousand became refugees and fled westward in a desperate search for work and a new life for their families. When they arrived they were denigrated and exploited by another group of big landowners that had already stolen California from Mexico and already imported their own cheap labor. This is happening the world over today and is still happening in America where we may yet see a repeat of the 1930s.

In two generations, the real and fictional farmers on the plains had slipped from being land owners to tenants to laborers as they borrowed to support their failing farms and were then turfed off by the banks. In Oklahoma they farmed corn and wheat and grew vegetables for themselves. In California, they had a different experience – even though they were still working in the fields their degradation continued. “A man may stand to use a scythe, a plow, pitchfork; but he must crawl like a bug between the rows of lettuce, … he must go on his knees like a penitent across a cauliflower patch”

Rolling through Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle with howling hot dry winds it was easy to see how the dust bowl could happen. One of Steinbeck’s characters said “Maybe we oughtn’t a broken up the land”. Today the land is pockmarked with hundreds of fracking tanks and the land is held together by irrigation. But this area is in a ten year drought so groundwater is just fending off another catastrophe. The Ogallala aquifer is running out of water fast but industrial agriculture can’t slow down – the shareholders won’t allow it. These are exactly the same forces that drove the Joads from their land. Only a matter of time.

Once you leave the plains heading west, Route 66 heads into New Mexico and Arizona and the Mojave Desert – a truly brutal environment – and it is painful to imagine a 1935 journey across this heat and this landscape in a broken down car cut apart with a truck bed with a failing motor and no money for food, let alone tyres and repairs. None of us really understands the migrant experience.

At Barstow the Joads headed north to the Central Valley they thought was going to be salvation. They went to Bakersfield, to shanties, and into poverty. Less than10% of the migrants stayed in California and most drove back.

We continue on Route 66 from Barstow to Pasadena and Santa Monica with lots to think about.

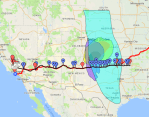

The map shows the fictional route of Tom Joad and his kin – Route 66 from Oklahoma to California. The colored shapes show the extent of the dust bowl – it started small in 1935-36 where Kansas meets Texas but spread across the plains by the end of 1938 before shrinking back to where it started by 1940.